What is Flat Head Syndrome (FHS)? |

|

It is quite normal for your baby’s head to have small left to right side imperfections. The top part of the infant’s skull (calvary) is formed by soft and flexible bones with spaces between them called cranial sutures. These form larger gaps at their intersections called fontanelles. These spaces allow the infant’s head to change shape, and even “telescope” under one another to help go through the relatively narrow birth canal during vaginal delivery. This may result in a “funny” head shape, which should resolve within the first couple of weeks post-birth. When an abnormal shape persists, it is important to find out the cause and treat it appropriately.

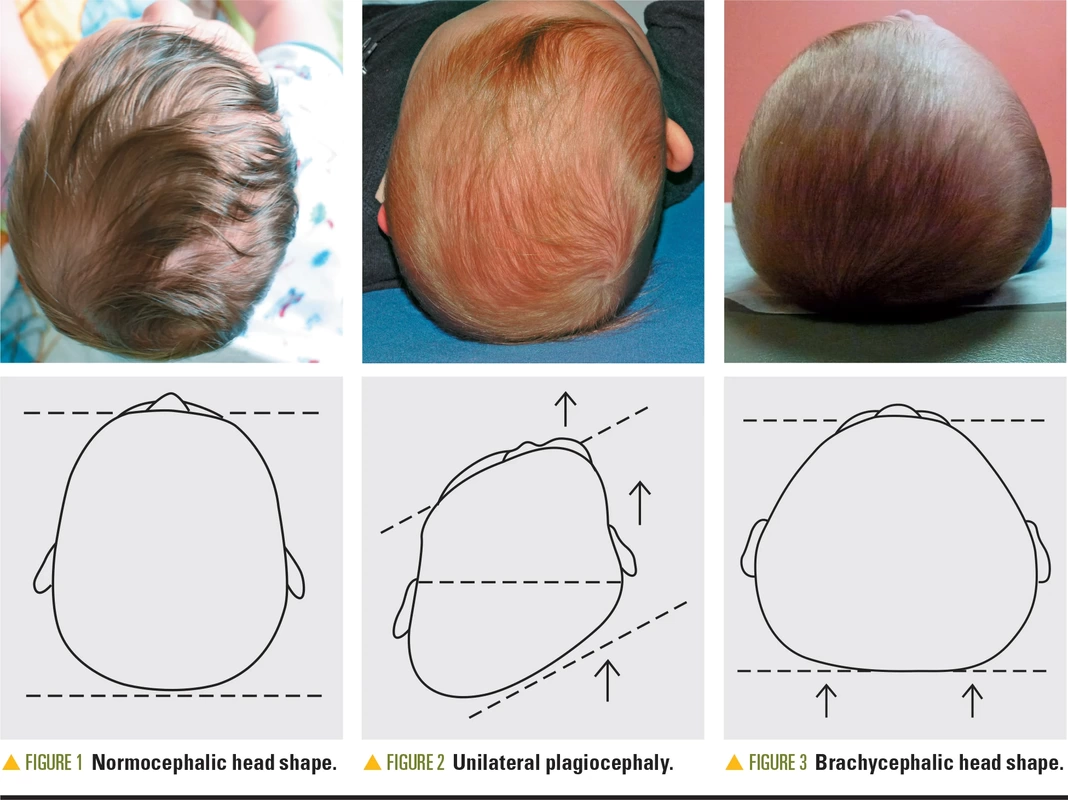

The spaces between the bones also allow for a rapid increase in brain growth, as the infant’s brain increases by 101% in the first year of life. Also during that time, the calvarial bones start a process, which could be described as interdigitation, at the sutures. The bones are fully interlocked at around the middle of second year. During this year the brain growth increases by further 15%, reaching 83% of an adult’s brain volume (Knickmeyer et al., 2008). FHS refers to a flattening on the back of the head (the cranial bone there is called the occiput) - in the centre – brachycephaly, or on either side of the back of the head - plagiocephaly, see picture below. The asymmetrical flattening may also involve varying degrees of forehead protrusion and asymmetry of ear position on the same side, and some facial asymmetry. The asymmetry can be referred to as deformational, positional or non-synostotic (which is the opposite of craniosynostosis explained below) plagio/brachycephaly. Other form of head asymmetry is dolichocephaly, also referred to as scaphocephaly, this is an elongated and narrow head shape usually seen in prematurely born babies - this will not be discussed in this article. There can be more than one form of asymmetry present. Picture from:

https://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/pediatrics/pediatric-epidemic-deformational-plagiocephalybrachycephaly-and-congenital-muscular-torticollis FHS may affect 1 in 5 infants in the first 1-6 months of life, but the exact prevalence remains unclear. It is mostly visible when looking from above and can be measured in millimetres using a craniometer or calipers. It is generally graded as mild, moderate and severe, although there isn’t an internationally recognised standardisation of categorisation. Research indicates that FHS does not always correct spontaneously (Royal Cornwall Hospital NHS Trust, 2017).

|

Possible causes and risk factors. |

|

There are many reasons why cranial asymmetries may arise, mostly from prenatal (late gestational) and/or postnatal mechanical forces applied to the infant skull.

Cranial pressure may happen already inside the mum’s womb depending on how the infant has been lying in utero. Some women might have pre-existing restrictions or complications, such as severe scoliosis, previous major uterine surgeries, pelvic/abdominal mass(es) like large fibroids, or abnormally shaped uterus. Sometimes there is not enough amniotic fluid (oligohydramnios), which restricts the space in the womb and leaves less cushioning for the baby. And of course, the space gets a little competitive with multiple pregnancies, such as twins or triplets. The head can also be subjected to increased pressure during labour, especially with an unusual birth position, prolonged labour (or very fast labour), or during assisted vaginal delivery with vacuum extractor cup (such as Ventouse or Kiwi OmniCup) or forceps. Prematurity is also a factor as the baby’s head is softer before full-term and therefore more responsive to pressure. There can be a muscle problem in which the baby has a spasm or a mass in a neck muscle called sternocleidomastoid. The mass is referred to as a “tumour”, which is an unfortunate term and can concern the parents. The medical term is fibromatosis colli and it is a benign, mostly self-limiting condition. It can lead to torticollis. Usually a spasm or a mass in the left muscle would lead to baby’s ability to turn head to the right side but not the left. If you notice that your baby turns their head only to one side, please do raise it with your midwife, home visitor or your GP, as the earlier the intervention the better the outcomes. The incidence of flat head syndrome has increased in the past few decades, after the success of the “Back to Sleep” campaign introduced in 1994. This campaign promoted putting babies to sleep on their backs, which has been a successful measure to reduce Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Sometimes, FHS is a result of simple positional lie preference or the fact that the baby’s crib is by the wall and they mostly look one way, i.e. into the room or at parents/siblings, away from the bland wall. Being male is also listed as a possible factor, the hypothesis being that baby boys' heads are larger and less flexible. This difference might make them more susceptible to compressive forces in utero and during delivery, and the rapidly growing male head may increase gravitational forces further contributing to positional FHS, especially with an already established position of comfort. However, there can also be a more severe but RARE condition called craniosynostosis, in which the cranial bone sutures fuse prematurely. In some cases this might just result in a mildly abnormally shaped head, while in other cases the brain development can be affected, which can result in developmental impairments. This condition may also sometimes be associated with different syndromes and once suspected, it requires a referral to a specialist for further investigations, monitoring and treatment. Another rare condition is hemivertebra, our spine consists of "building blocks" called vertebra (there are 7 vertebrae in our neck), and this rare condition is when the baby is born with only half of the vertebral body. There are usually other signs and symptoms related to this condition, imaging is needed to confirm the diagnosis, and this is usually discovered in hospital when the baby is born. Other contributing factors have been identified, for example:

Parents are generally advised by medical practitioners not to worry about mild cases, as FHS is understood to be self-resolving with age with simple measures, which I discuss later. However, there is emerging evidence that adding appropriate paediatric manual therapy to standard conservative management strategies as an early intervention for positional plagiocephaly/ muscular torticollis, not only prevents worsening of symptoms but leads to improved achieved range of motion, improvement in head shape and parents’ satisfaction (Antares et al., 2018; Ellwood et al., 2020; Pastor-Pons et al., 2021 1&2). Paediatric Osteopathy.When you take your baby to a paediatrically trained Osteopath, their aim is to find which of the above is/are the likely cause(s) of your baby’s presentation. This is important as it informs the prognosis and treatment plan. They will ask detailed questions not only about why you brought your baby, but also about how your baby is feeding, sleeping, passing stool, and generally thriving. They will go through the pregnancy and birth, illnesses, injuries and much more.

The Osteopath will then examine your baby, from feet all the way to the top of their heads. It is their job to find any tension in their body that is potentially the cause of why the baby hasn’t resolved the issue him/herself naturally within first 1-2 weeks of life. They will discuss their findings, treatment plan and possible side effects. Only when you are happy to go ahead and give consent, will the treatment start. They have been trained to look out for cases that require referral and if they suspect that further investigations or referral is needed, they will communicate this with you. There are times when a presentation is not straightforward and it can take a couple of appointments to monitor the progress before a referral is appropriate. Sometimes the first treatment might consist of treating the pelvis only. I know, that is a little far away from the neck and head, but imagine wearing a coat and putting your hand in your right pocket and pulling it downward, the tension created in the fabric of your coat will be visible all the way from your right pocket across to your left shoulder, and yes, it is possible that a problem in the neck is greatly contributed to by tension in the pelvis through the connective tissues in the body. After the treatment, you will also be given advice on how you can help - and there is a lot parents can do. You might also be given exercises, but I will not be covering these here as they are patient/baby specific and not every exercise fits every baby. What parents can do - positional therapy.There is a lot you can do every day; it is called repositioning or counter-positioning therapy. As the name suggests, the main aim is to position your baby to encourage her/him to stay off the flattened part of their head and therefore put weight on the bulging side instead. This should be started immediately after you notice any lie preference or head asymmetry. However, if the baby resists this, please do not force this and seek help with a paediatric manual therapist instead, who can help with this.

Doing tummy time as soon as you get home from hospital is important and is deemed to be safe if you have a healthy baby. Tummy time should always be supervised and when the baby is awake. It not only helps with the next developmental milestones such as crawling etc., but it trains and strengthens the neck, shoulder and arm muscles. Not every baby likes tummy time, so one can start for a few seconds after each nappy change, building it a little longer day by day. To support your baby to stay upright and prevent early exhaustion, roll a towel and put it between your baby’s arms and body – under their armpits so that it holds them upright, shaping it into a horseshoe so the baby is stabilised on both sides. You can "fold their arm" so that they are in front of them, elbows touching the ground. If your baby is unsettled, please read my article on Unsettled baby. Don’t forget that having your baby on your chest whilst you sit back on the sofa also counts as tummy time, and so does putting them facing down on your lap, but well secured with your hands. You can use games, toys, laughs and clapping to encourage your baby to be interested in tummy times. You can always try a few seconds, pick them up, have a cuddle and try again. Another tummy time tip is to carry her/him on your forearm facing down, one hand under the tummy and other on top, to keep them secure. I am aware that this can be very tiring after a couple of minutes. This is when slings and front carriers come in handy, having a baby in a sling means that they are more upright, their head is not contacting the ground therefore there is no direct pressure exerted on it and to some level they also train their neck strength. I recommend that you find your local “sling library” and use that service. A sling specialist can help you find the right sling. You may be able to rent a sling before committing to buying one, and also get advice on a sling that you might already have but that just doesn’t feel quite right, whether to you or your partner, or both. It is also good to check if the sling you were handed down/given/bought is suitable for your baby’s age, her/his hip development, correct neck position to prevent breathing obstructions but also excessive neck extension etc. Follow Orkney Babywearing Support Facebook group and join Orkney Sling Library to find out about sling drop-in sessions. If you need a specialist advice due to your personal circumstances, such as post C-section or if you have any other specific health concerns, I'd be very happy to recommend Madeline from https://sheenslings.com. Madeline is based in England and does fitting online - I worked with her in the past and feedback from parents has always been wonderful. Make sure you change your baby’s position as much as possible in order to avoid constant pressure on one part of the body. Consider how your baby is in her/his cot. Are they always facing the same side? For example, most cribs/cots are placed against the wall, so positioning the baby with her/his head to the foot or to the head of the bed, on alternating days, is recommended. This encourages the baby to lie on the side of the head that enables her/him to look into the room or at you. Alternating the position should encourage lying equally on the two sides of the occiput. The same rule applies to their pram/car seat/play chair/play mat. Change the position of their toys to encourage them to turn their head to the non-flattened side. You can also put a wrist rattle on the side they look less, as the sound and then contrast/colours are likely to get their attention. But please make sure you check for choking hazards: there should be no loose items around with the baby unsupervised. When your baby is fast asleep, and only when they are fast asleep, you can gently turn their head on the non-flattened side. If they are half asleep they are likely to turn back, resist it or become irritable. They will certainly turn their head back, be persistent but try not to get consumed by it. There are times when using car seats or baby chairs cannot be avoided, but generally try to make sure that you limit these times to a minimum. Also try to play with your baby as much as possible as stimulation helps with movement and neuro-motor development. Change sides/positions during bottle feeds. Also check the position you burp your baby in - are they alway over the same shoulder, looking the same way? Should you ever need advice on feeding, whether breastfeeding or bottle feeding, please attend your local weekly infant feeding support group meetings, speak with your midwife or health visitor. Or contact an IBCLC specialist for an online appointment via their register https://lcgb.org/find-an-ibclc/. I'd be very happy to recommend Anna Page on 07963 800 243 or [email protected], with whom I collaborated in the past, Anna is based in England. With positional therapy alone, you need to be patient in monitoring how effective the above measures are. Research suggests that it can take 6-8 weeks before any improvement is visible, and the earlier the intervention starts the quicker the results. Head shape can continue to improve up to 2 years of age, and a Dutch study suggests that by 5 years of age, the severity of positional plagiocephaly is within the normal range in 80% of children, within the mild range in 19%, and within the moderate to severe range in only 1% (van Vlimmeren et al., 2017). However, these results are not transferable to other countries as the Netherlands have a good awareness about infant asymmetry in early life and therefore early intervention is common. To monitor the head shape and its changes, you can look into craniometer (eBay is a good option, but make sure you ask the seller how old the device is as the band can become overstretched and brittle with age/use) or Skully Care, which is a mobile app free for parents. If your baby is diagnosed with torticollis, your doctor is very likely to refer you to a paediatric physiotherapist under the NHS. Depending on the findings, further investigations might take place, such as an ultrasound. Treatment varies, depending on the cause, from observation, orthosis, massage and stretching exercise programs, botox injections, and various surgical procedures. Stretching programs with a physiotherapist are reported by a Korean study to be sufficient in 90% of cases, subject to the type of torticollis and early intervention (in Kim et al., 2019). There are also devices that parents can explore, such as Mimos pillow or SleepCurve baby mattress. Mimos pillows come in different sizes for different age groups. The company claim to have high safety standards and that they use materials with breathable structure preventing accidental suffocation. I personally am unable to advise parents on whether they should invest in those or not. They can be expensive and the baby might simply push them to the side every time you use them. There are other similar products on the market, but independent research is missing. Should you wish to try one, I would recommend that you borrow one when possible or buy second hand and see if it works for you and your baby. Being a paediatric Osteopath, I certainly suggest that even when you adhere to the above, you should still seek advice from a paediatrically trained manual therapist - whether an Osteopath, Physiotherapist, Chiropractor or an Occupational Therapist. But I cannot stress enough, they must be paediatrically trained, as babies are not just small adults. I also find in my clinic that when treatment is combined with treatment by a paediatric physiotherapist or occupation therapist, improvements are achieved quicker and the results are better overall (this doesn’t apply only to FHS but other musculoskeletal issues, too). In moderate and severe cases, some parents may choose to opt for a helmet therapy treatment to address the aesthetic/cosmetic issue. They might be concerned about the psychological effect a facial asymmetry may have on their child later in life, as well as possible bite problems, which in future years may need dental/orthodontic work. Currently, the NICE (the National Institute of Clinical Excellence) guidelines do not make any recommendations on the use of helmets, as there is not sufficient evidence collected to state whether they can further improve the shape of the skull (Royal Cornwall Hospital NHS Trust, 2017). To my knowledge, helmets are not prescribed on the NHS and our nearest service is provided in Glasgow by Technology in Motion. With the helmet therapy, a few aspects need to be considered. The cost is approx. £2,600. The helmet needs to be worn for up to 23 hours per day for a few months. The baby and the helmet need to be reviewed on a regular basis to check the progress and adjust the helmet not to restrict growth and to prevent pressure sore, skin irritation etc. This is usually fortnightly and later monthly, but can be weekly if your baby is going through a growth spurt. And the baby might find the device uncomfortable. Technology in Motion offer free assessment for babies between 4 and 14 months, outside of this age range the fee is £120. There is no obligation to then go ahead with treatment, but if you decide to go ahead, the fitting will take place the next day, you'll also need to pay the deposit and the remainder of the cost within 2 weeks (a deposit with 3 instalments option is also possible at slightly increased cost). Finally, in case of craniosynostosis, the diagnosis is confirmed by imaging and the baby will need to be sedated during the procedure. In very mild cases, the baby may only be monitored and no treatment be required, however, when brain development is affected resulting in developmental impairment, surgery is warranted. But let’s stress again here, this condition is very rare. Summary.In summary, there are many causes of external cranial pressure that may lead to FHS, from the environment in utero, to restrictive birth, neck muscle problems after birth, babies sleeping on their backs due to the life saving “Back to sleep” campaign, and even a rare premature fusion of cranial bones or hemivertebra.

Parents can make a lot of improvement with positional therapy during the day and night. The main aim is to limit the time your baby spends in positions creating pressure on the flattened part of their skull. It is recommended that parents make sure that the baby is active, doing tummy time and changing position regularly. They can achieve that by putting all stimulation to the opposite side, limit time in car seats, change sides when bottle feeding and gently turn their heads when they are asleep. Slings and anterior baby carriers are very helpful to prevent parents’ fatigue. Mimos pillows might be suitable for some and some parents may opt for special mattresses or the helmet therapy. Seeking help from a paediatrically trained manual therapist is beneficial in case of torticollis, if the above measures are not as effective as expected and FHS is potentially resulting from tissue tension in the infant’s body. The earlier the intervention, the quicker the improvements. For further reading, please find below links to the NHS website on FHS, handbooks by GOSH and The Royal Cornwall Hospital NHS Trust, for parents and practitioners. There is also some information from the USA on tummy time - if you explore their website further, please be aware that advice on medication and treatment may vary in the UK.

Please note that the above is only general information and is not intended to diagnose, that can only be done after a detailed case history and examination. If you have any concerns, speak with your midwife, health visitor or GP. The information is accurate at the time of writing in April, 2020, with minor Orkney specific service updates made in July 2023 (further research update due later in 2023). I have no financial or other interests in any of the practitioners/products mentioned above. Antares, J.B., Jones, M.A., King, J.M., Chen, T.M.K., Lee, C.M.Y., Macintyre, S. and Urquhart, D.M., (2018). Non‐surgical and non‐pharmacological interventions for congenital muscular torticollis in the 0‐5 year age group. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(3). Ellwood, J., Draper-Rodi, J. and Carnes, D., (2020). The effectiveness and safety of conservative interventions for positional plagiocephaly and congenital muscular torticollis: a synthesis of systematic reviews and guidance. Chiropractic & manual therapies, 28(1), pp.1-11. Kim, S. M., Cha, B., Jeong, K. S., Ha, N. H., & Park, M. C. (2019). Clinical factors in patients with congenital muscular torticollis treated with surgical resection. Archives of Plastic Surgery, 46(5), 414–420. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2019.00206 Knickmeyer, C., R., Gouttard, S., Kang, C., Evans, D., Wilber, K., Smith, K., J., Hamer, M., R., Lin, W., Gerig, G. & Gilmore, H., J. (2008) A structural MRI study of human brain development from birth to 2 years. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28 (47) 12176 – 12182. Launonen, A. M., Vuollo, V., Aarnivala, H., Heikkinen, T., Pirttiniemi, P., Valkama, A. M., & Harila, V. (2019). Craniofacial Asymmetry from One to Three Years of Age: A Prospective Cohort Study with 3D Imaging. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010070 Mawji, A., Vollman, A.R., Fung, T., Hatfield, J., McNeil, D.A. and Sauvé, R., (2014) Risk factors for positional plagiocephaly and appropriate time frames for prevention messaging. Paediatrics & Child Health, 19(8), pp.423-427. McGarry, A., Dixon, M.T., Greig, R.J., Hamilton, D.R.L., Sexton, S. and Smart, H. (2008), Head shape measurement standards and cranial orthoses in the treatment of infants with deformational plagiocephaly. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 50: 568-576. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03017.x Pastor-Pons, I., Lucha-López, M.O., Barrau-Lalmolda, M., Rodes-Pastor, I., Rodríguez-Fernández, Á.L., Hidalgo-García, C., Tricás-Moreno, J.M. (2021). Efficacy of pediatric integrative manual therapy in positional plagiocephaly: a randomized controlled trial. Ital J Pediatr. 2021 Jun 5; 47(1):132. Pastor-Pons, I., Hidalgo-García, C., Lucha-López, M.O., Barrau-Lalmolda, M., Rodes-Pastor, I., Rodríguez-Fernández, Á.L., Tricás-Moreno, J.M. (2021). Effectiveness of pediatric integrative manual therapy in cervical movement limitation in infants with positional plagiocephaly: a randomized controlled trial. Ital J Pediatr. 47(1): 41. Royal Cornwall Hospital NHS Trust (2017) Plagiocephaly and Brachycephaly – Guideline for Health Care Professionals. Cornwall: Royal Cornwall Hospital NHS Trust. van Vlimmeren, L. A., Engelbert, R. H., Pelsma, M., Groenewoud, H. M., Boere-Boonekamp, M. M., & der Sanden, M. W. (2017). The course of skull deformation from birth to 5 years of age: a prospective cohort study. European Journal of Pediatrics, 176(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2800-0 Van Vlimmeren, L.A., van der Graaf, Y., Boere-Boonekamp, M.M., L’Hoir, M.P., Helders, P.J.M., Engelbert, R.H.H. (2021). Effect of pediatric physical therapy on deformational plagiocephaly in children with positional preference: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 162:712–8. van Vlimmeren, L.A., van der Graaf, Y., Boere-Boonekamp, M.M., L’Hoir, M.P. Helders, P.J. and Engelbert, R. H. (2007) Risk Factors for deformational Plagiocephaly at birth and at 7 weeks of age: a prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 119(2), pp. 408-418. |