What PGP is, its cause and treatment. |

|

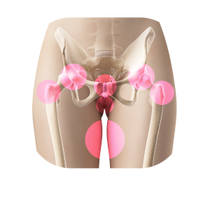

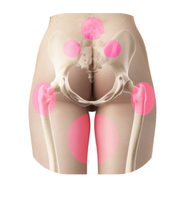

PGP is an umbrella term for pain originating from and presenting around the pelvis, see pictures below for pain distribution. It used to be called SPD (symphysis pubic dysfunction), but this was a term incorrectly suggesting that only one joint is involved. PGP is a subcategory of lumbopelvic pain, which can present in both men and women and generally arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis or osteoarthritis (Vleeming et al., 2008).

Risk factors for developing PGP during pregnancy are a history of previous low back pain (LBP) and/or trauma to the pelvis. It can occur separately or in conjunction with LBP, and is mostly referred to as a pregnancy related condition, however, it can continue into or start during or after giving birth.

The symptoms may be noticeable during everyday activities, but are worse when walking, standing on one leg (e.g. when putting trousers or socks on or walking up and down the stairs), movement with your legs apart (e.g. when getting in or out of your car or a bath), or turning in bed. The level of pain can vary from mild to extreme. It is estimated that 1 in 5 women (20%) experience PGP during their pregnancy (Vleeming et al., 2008). It is quite common, BUT NOT NORMAL, and should be raised as soon as the symptoms start with your midwife, GP or a health visitor. Historically, PGP was believed to be hormonally driven, and women were incorrectly advised to “bear with the pain” as it would go away post labour. Although the majority of women recover spontaneously soon after labour, approximately 20% report pain lasting for years post-birth (in Stuge et al., 2017). This “traditional” approach, when women are given advice, painkillers, belts, crutches and wheel chairs without hands-on treatment results in a cascade of issues. These include unnecessarily prolonged pain and fatigue during pregnancy, inability to care for their family, becoming housebound and socially isolated, and dependant on others. There is also psychological distress, leading to deteriorating mental and physical wellbeing, affecting not only the woman but also her whole family. Although the current research acknowledges that hormonal changes play a role in this process, PGP is now widely understood to be a mechanical issue, and as such, the large majority of cases can be treated with manual therapy. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist recommend manual (hands-on) therapy as a treatment method for PGP. This should be performed by physiotherapists, osteopaths or chiropractors who specialise in PGP in pregnancy (RCOG, 2015). If the NHS route is not available, or your appointment is too far in the future, you can always opt to go privately. Talk to your midwife, GP or a health visitor for an appropriate referral. They will discuss your symptoms with you and once other causes are excluded, they will refer you to women’s health physiotherapist. Other potential issues that they will consider include gynaecological, urological, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, neurological, psychological and other causes, such as abuse. Late treatment can prolong recovery time, increase the number of treatments needed, and increase the need for pain relief. The aim is not only to prevent PGP from worsening, but to relieve it quickly and definitely. Relief will help leave you pain free going into labour, as women with PGP are more likely to be considered for induced labour, which is unnecessary for PGP alone. Research suggests that induction may be less efficient and more painful than spontaneous labour, with epidural analgesia and assisted delivery more likely to be required. When induced using pharmacological methods, about 15% of women have instrumental births (foreceps/ ventouse) and 22% emergency caesarean sections. Induction therefore has to be clearly clinically justified (NICE, 2008). PGP can be especially problematic for women who are on the hypermobility spectrum or have been diagnosed with hypermobility Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS). These women are 3 times more likely to develop PGP (in Pezaro et al., 2018). One cause of PGP is Diastasis Symphysis Pubis, when the joint at the front of your pelvis separates more than 1cm. This can be a complication in pregnancy as well as during and after labour. Other processes that need to be considered include degenerative, metabolic, genetic and biomechanical factors (in Verstraete et al., 2013). And in some cases, PGP can result from how the baby lies in utero and exerts pressure on some abdominal/pelvic structures. Again, these structures can be worked on with manual therapy to offer relief. If you are experiencing PGP in your first pregnancy, you are in a higher risk for your future pregnancies, but that doesn’t correlate with its intensity. |

How the female body changes and how Osteopathy can help. |

|

The female body goes through an incredible series of changes during pregnancy. The baby is growing every day in the uterus, which grows upward and outward in the abdomen rearranging organs to the sides, changing the centre of gravity to the front and creating a larger curve in the lower back. The breasts are also enlarging, creating further weight on the front and therefore increasing tension in the upper body and upper back and neck. In some women these changes can lead to thoracic outlet syndrome, causing symptoms in their arms, hands and fingers. At the same time, there is an increase in hormones that enable the tissues to go through such changes, such as relaxin and progesterone.

Rest assured, a woman’s body has the ability to adapt to the physiological changes during pregnancy. These changes affect your body from your feet all the way to the neck and how you hold your head. However, there can be residual effects from earlier injuries, which your body could not resolve fully but managed to compensate for well so that you felt you recovered. Now that your body has to adapt to new demands within a relatively short period of time, it may be struggling a little. It could also be as simple as that you lifted a shopping bag in an unfavourable position or angle, sat in a chair at work for too long, or slept awkwardly and created some tension or imbalance in your pelvis that your body cannot resolve by itself, and that is just getting worse. Being an Osteopath with special training in women’s health, I find that there are no two women with PGP who have exactly the same cause. Some women I only treated once and they were pain free for the rest of their pregnancy, although most needed between 3-5 treatments. On some occasions I treated them regularly throughout their pregnancy, such as those with shift work and physically demanding jobs. Sometimes, women book because their NHS appointment is in some weeks in the future and they want to relieve the pain immediately. The first appointment is 70 minutes long, I will be asking questions about your concerns and your medical history, including your general health, accidents, injuries, operations, etc. You may be asked to dress down to your underwear at the start of the examination, please feel free to bring shorts and a vest to change into for your comfort. A physical examination will follow consisting of some guided active and passive movements and hands-on palpation. I will examine your feet, knees, hips, pelvis, pelvic floor (externally only) and lower back on your first appointment. We will then discuss my findings. I will explain how I can help and over what period of time, outlining a treatment plan and any possible side effects. Once agreed and consent is given, you will also be treated. I will refer you to another specialist if necessary. After the treatment, you will be given some advice on what you can do to help yourself and what to avoid (see below). I am likely to give you some exercises later, but that will only take place once I am happy that your body is well balanced and it is appropriate to start strengthening. For this reason, I will not be covering exercise in this article. What you can do.This section provides helpful tips on how to manage your symptoms doing everyday tasks. But I must stress, it does not replace manual therapy, which addresses the cause of your pain.

This is not an exhaustive guide, and I encourage you to use the further resources below. Further Resources.The Pelvic Partnership is a wonderful UK charity that provides a lot of information and support for women with PGP. They provide extra tips and the information is based on feedback from thousands of women.

https://pelvicpartnership.org.uk/ You can also find a list of practitioners in the UK, who work with women with PGP. The list only contains practitioners who were recommended by women whom were helped with PGP by those practitioners: http://pelvicpartnership.org.uk/list-of-recommended-practitioners/ A list of osteopaths, who completed a 2-year postgraduate diploma in women's health can be found here: https://www.molinari-institute-health.org/news This link has demonstrations on movement and positioning, please do have a look. http://brochures.mater.org.au/brochures/mater-mothers-private-brisbane/pelvic-girdle-pain-physiotherapy-hints-to-relieve And lastly, a short information leaflet by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists for women with PGP. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/patients/patient-information-leaflets/pregnancy/pi-pelvic-girdle-pain-and-pregnancy.pdf If you have any comments or recommendations in relation to my articles, please do get in touch, your feedback is always appreciated. Please note that the above is only general information and is not intended to diagnose, that can only be done after a detailed case history and examination. The information is accurate at the time of writing in May 2020 with minor updates due to location change in March 2023. I have no financial or other interests in any of the practitioners or products mentioned above. References.Antonucci, R., Zaffanello, M., Puxeddu, E., Porcella, A., Cuzzolin, L., Pilloni, M., D. & Fanos, V. (2012). Use of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in Pregnancy: Impact on the Fetus and Newborn. Current Drug Metabolism, 13 (474).

Bergström, C., Persson, M., & Mogren, I. (2014). Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy - pain status, self-rated health and family situation. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 14 (48). NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2008). Clinical Guideline CG70: Inducing Labour. NICE: Manchester. Pezaro, S., Pearce, G., & Reinhold, E. (2018). Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome during pregnancy, birth and beyond. British Journal of Midwifery, 26(4), 217-223. RCOG. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (2015). Information for you: Pelvic girdle pain and pregnancy. RCOSG: London. Stuge, B., Krogstad, H. & Grotle, M. (2017). The Pelvic Girdle Questionnaire: Responsiveness and Minimal Important Change in Women With Pregnancy-Related Pelvic Girdle Pain, Low Back Pain, or Both. Physical Therapy, 97(11), 1103–1113. Tinkle, B., Castori, M., Berglund, B. et al. (1017). Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (aka Ehlers–Danlos syndrome Type III and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome hypermobility type): Clinical description and natural history. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 175(1), 48-69. Verstraete, E. H., Vanderstraeten, G., & Parewijck, W. (2013). Pelvic Girdle Pain during or after Pregnancy: a review of recent evidence and a clinical care path proposal. Facts, views & vision in ObGyn, 5(1), 33–43. |